Fecal Transplants May Cause Long-Term Health Risks, Says New Study

Fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) are often promoted as promising treatments for a range of conditions like obesity, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and even autism. But a recent University of Chicago study suggests caution. The research warns that FMTs could have unintended, long-lasting effects on a person’s metabolism, behavior, and gut health.

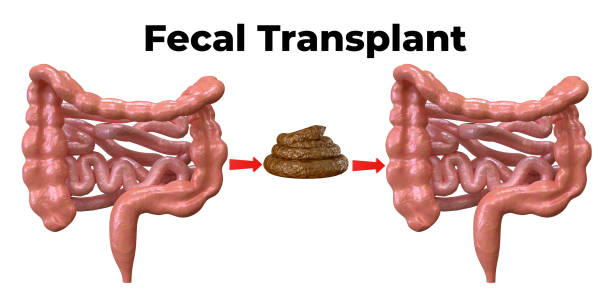

FMT works by transferring stool from a healthy donor to a sick patient, aiming to restore a balanced gut microbiome. But since most microbes in stool come from the large intestine and can’t tolerate oxygen, they may end up colonizing parts of the gut where they don’t belong — like the small intestine.

In both animal studies and lab tests on human tissues, researchers found that transplanted microbes survived in these non-native regions for months. They even changed those environments to suit themselves, potentially disrupting the host’s normal digestion, immune function, and energy use.

The study’s lead author, Dr. Orlando DeLeon, called for more careful matching of microbes to the right areas of the gut, instead of using a “one-size-fits-all” approach.

Right now, the FDA only approves FMT to treat recurring C. difficile infections. But due to early successes, it’s been used more widely in other conditions — possibly prematurely. This research shows the gut is a complex system with distinct regions, and mismatching microbes could cause more harm than good.

The authors recommend a new strategy: omni-microbial transplants (OMT) — a more tailored approach that uses microbes from every part of the gut. These would be more likely to settle in the right place and restore proper balance.